Shepherding Souls to Safety: 3 Ways to Foster Psychological Safety in the Modern Workplace

By: Ryan Brence

“There are two kinds of people in the world. One walks into a room and says, “There you are!” The other walks into a room and says, “Here I am!”

Have you ever dreaded attending a meeting due to the fear or anxiety of how you or your thoughts & opinions would be judged by the leader?

It seems like a rhetorical question because I know most, if not all of us, would respond with a resounding YES.

For me, this took place on a weekly basis over the course of a year during my time as an executive officer in the Army.

The brutal “Maintenance Monday” meeting…

Each week, I would be charged with reporting the status updates of millions of dollars worth of equipment within my respective unit. This included the repair or replacement of parts needed for multiple weapons systems, armored vehicles, and miscellaneous operational equipment.

While the responsibility and importance of my unit’s preparedness was not lost on me, I oftentimes had a hard time fully understanding the faults and breakdowns associated with the equipment.

Let’s just say that I’m not the most mechanically inclined…

However, with that being said, I would show up to “Maintenance Monday” meetings prepared to report on my unit’s equipment after having multiple conversations with my company’s operators and mechanics.

The soldiers I worked with would explain the faults to me in great detail by showing me the specific breakdowns and reviewing each problem with me in the corresponding equipment manuals. Then, I would do my very best to explain the issues to my superior officer in our weekly meetings.

Regardless of how prepared I felt, more often than not I would leave those meetings feeling frustrated, embarrassed, and discouraged. My emotions resulted from the tone set and the responses given by my leader.

Most of the times I reported my unit’s maintenance status, my authority figure would end up either interrogating, interrupting, or chastising me in front of my peers. In the rare occurrences that I made it out without questioning or blame, I was witness to another peer casualty being reprimanded without the opportunity to fully explain the situation or seek the assistance needed.

Over time, my fear and anxiety for these maintenance meetings stifled my curiosity, learning, and overall growth because I simply sought out the critical information that I knew would be most heavily scrutinized. There were also times that I would purposefully not report minor maintenance issues to avoid the retaliation that I knew would come from a longer list of equipment issues.

In the end, both my professional development and my unit’s overall mission readiness were stymied by my superior officer in these meetings. The weekly occurrences drained me of energy, confidence, and the desire to think creatively.

My voice simply did not feel heard. Can you relate?

Psychological Safety

In another Intentional Leader article, Wes Cochrane described how leadership is a profoundly human endeavor. We’re not dealing with robots - We’re dealing with souls. And all of our souls have truly been tested in recent years.

From the pandemic, geopolitical instability, and racial/ethnic tension (just to name a few), future uncertainty and fear of the unknown have catalyzed new collective movements in which individuals are seeking safety in a multitude of different ways.

Specifically, organizations across the globe are experiencing seismic shifts in turnover and productivity through the fallout of the Great Resignation and what is now being referred to as “quiet quitting.” While workplace wellness and employee engagement have been topics of discussion for many years prior to the pandemic, another term is being elevated in light of what’s currently at stake in the workforce - psychological safety.

Originally defined by William Kahn, and more recently developed and expanded upon by Amy Edmondson, psychological safety is “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.” For employees, risk taking could mean freely speaking up in meetings, suggesting new ideas or processes, or simply feeling accepted enough to show up to work as their true selves.

This type of security is cultivated through demonstrations of engagement, understanding, and inclusivity. While these types of behaviors are shown in many diverse ways, it is ultimately the leader’s responsibility to not only create, but also maintain, this type of organizational climate.

On the surface, the expression seems to be more of an academic term used by social scientists and psychologists. However, the benefits of high workplace psychological safety speak for themselves through various studies provided by Gallup and Accenture. Workplaces that foster this type of environment in their companies experience many benefits as shown below:

12% increase in productivity

27% reduction in employee turnover

40% decrease in safety incidents

57% rise in workplace collaboration

74% less stress on the job

In a recent study by Google’s People Operations, the human relations team set out to answer the following question: What makes a Google team effective? After over two years and hundreds of Google employee interviews, psychological safety was by far the most dominant finding for overall team dynamics. Other behaviors, such as setting clear goals and reinforcing accountability were important to Googlers, but unless team members felt psychologically safe, the other factors were insufficient.

With all the brilliant minds and incredible resumes found within Google, the most important factor for driving team performance (as told by employees) was the ability to feel safe taking risks and being able to be vulnerable in front of one another.

So, as we all navigate the new work environment and the many stressors placed on employees both personally and professionally, what steps can we take as leaders to promote and develop psychological safety in our organizations?

In Amy Edmondson’s book The Fearless Organization, she discusses three interrelated practices for building psychological safety: setting the stage, inviting participation, and responding productively. Let’s take a look at each of these practices more closely to discover practical ways to apply them in the workplace.

Setting the Stage

Setting the stage is critical for framing the work done both within the company and how it is perceived and valued externally by the team and clients. As leaders, we must emphasize the purpose of the operations being executed and for whom it ultimately impacts. While high returns on investment, profit margins, and annual bonuses can speak to employees’ extrinsic motivations, the intrinsic motivations found within mission, meaning, and purpose can galvanize teammates around a shared cause.

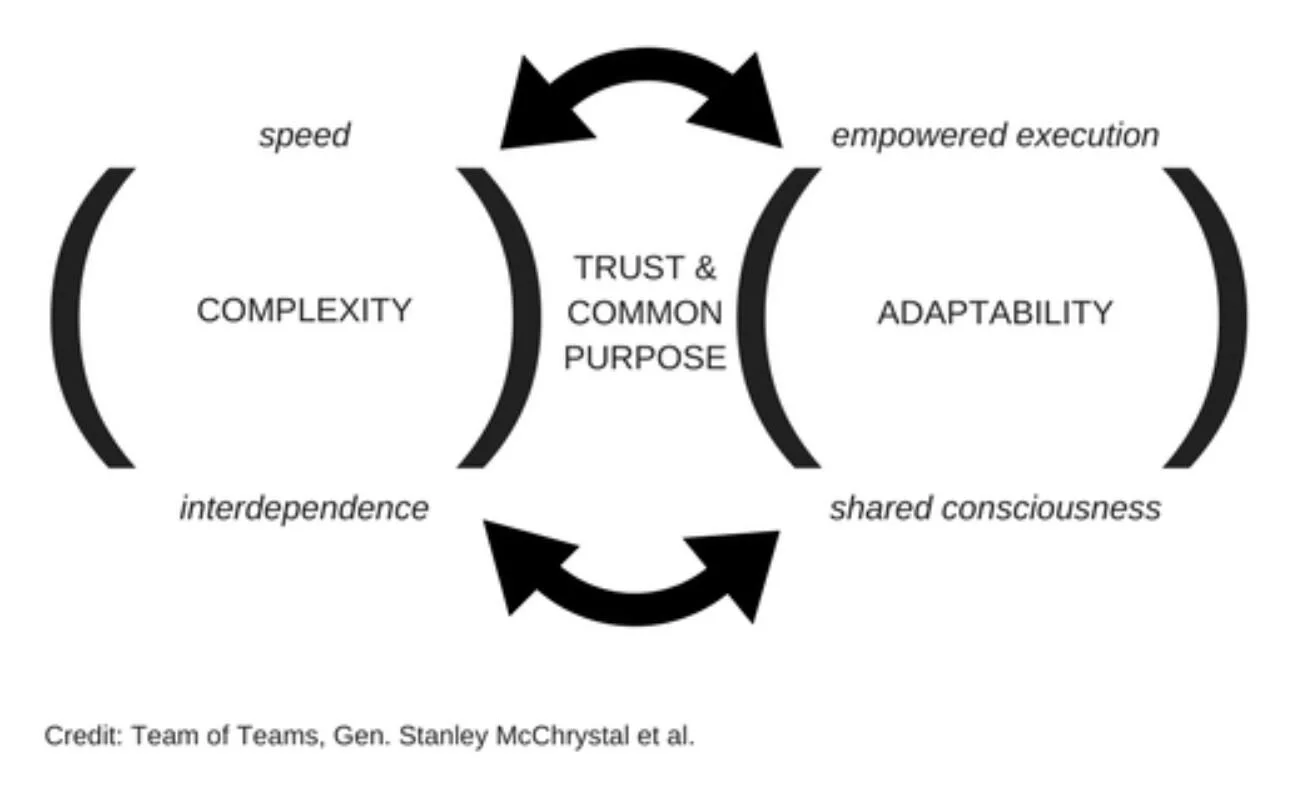

Additionally, setting expectations surrounding core values, standards, communication, and interdependence clarify what is most important internally while operating as a team. If employees know what is expected of them and how they contribute to the larger cause, then they will feel more ownership and buy-in towards fully contributing to the collective group.

The leader must always strive to display these expectations while also communicating grace that is found in the midst of failure. Since many people have natural instincts to avoid failure at all costs, reframing these mishaps as learning opportunities gives workers the freedom to take risks and strive for excellence in their day-to-day tasks and duties.

Leader Action Steps - Setting the Stage

Focus on what’s most at stake for your team through your organization's operations.

What is your team’s why? What big problems does your company help solve?

Set clear expectations around standards, failure, and team collaboration.

Be the Chief Reminding Officer by continuing to reinforce these critical points on a consistent basis.

Inviting Participation

The next step in fostering psychological safety in the workplace is inviting participation. Most employees have passionate and innovative thoughts and ideas that could improve the organization. However, the instinctive nature of self-protection can inhibit these ideas from being presented and discussed in environments that feel unsafe. Once again, it’s contingent upon the leader to not only set the stage for openness but also pull these thoughts and ideas out of team members through the power of questions within the appropriate forums and situations.

Amy Edmondson shares three leader tasks that she considers key for inviting participation: demonstrating situational humility, practicing inquiry, and setting up structures and processes. Situational humility allows the leader to acknowledge gaps in their own knowledge or understanding of how problems can be solved in specific situations. By openly addressing the unknown and soliciting feedback, employees feel empowered to present their own views to help fill in the gaps and help the company move forward.

When it comes to practicing inquiry, the leader’s full presence is key. Complete attention shown through body language, active listening, and validating responses give team members the affirmation needed to continue to provide thoughts and opinions knowing that their voice will be welcomed and encouraged for the overall welfare of the organization.

While situational humility and inquiry may commonly take place casually throughout the day through informal conversations, it is also important for leaders to establish formal structures and processes for ideas to be generated, tasks to be documented, and metrics to be tracked. By having consistent and productive meetings in which employees are aware of the agenda and items covered, team members can continue to show up prepared and confident that they can participate in ways that bring value to the group’s strategic goals and objectives.

Leader Action Steps - Inviting Participation

Admit personal mistakes and acknowledge when you simply don’t have the answers.

Show curiosity by asking open-ended questions to your team and team members. Be present, demonstrate positive body language, and respond with understanding.

Clearly communicate the purpose of set meetings and come prepared with a succinct agenda with known guidelines regarding time, tasks, and communication.

Intentionally allow space for team members to share thoughts and ideas.

Responding Productively

Edmondson's final task for leaders to cultivate psychological safety is responding productively. After inviting participation, the way we respond can express appreciation for our team members’ thoughts, ideas, and opinions. After genuinely thanking others for their feedback, leaders can take it a step further by helping brainstorm next steps that will give way towards impactful action for the organization.

Similar to situational humility, the leader can communicate the need for one or a group of team members to spearhead an initiative that progresses the organization closer to the goals and objectives set. By offering any help needed and responding with trust and permission to take action, the leader accomplishes a collective orientation towards continuous growth and learning for all employees involved in the process.

At this point, it’s important to point out that psychological safety may be construed as an overly soft expression for allowing everyone to be known, heard, and appreciated regardless of their input. I admit to initially feeling like this all sounds too good to be true and seems challenging to sustain in the workplace filled with problems and different personalities. However, Edmondson argues that psychological safety is not an “anything goes” environment where people are not expected to adhere to standards and meet deadlines.

The goal of psychological safety is not comfort. Instead, it is an enabler towards openness and candor that, if fostered correctly, can allow teams to thrive with a sense of shared purpose, mutual respect, and awareness of guiding principles and processes.

The key to cultivating this type of work environment is finding the proper balance of psychological safety and overall accountability.

As seen in the four-quadrant chart below, the top right “Learning Zone” represents the ideal state of team members feeling known and accepted while being held highly accountable for important and purposeful work. When this is accomplished, organizations strive for excellence by working effectively with one another to achieve the mission at hand.

The other quadrants show the imbalances of these two critical factors that can result in either comfort, anxiety, or even apathy. While every team member shares a certain level of responsibility in promoting psychological safety in the workplace, it is the leader that often sets the tone through Edmondson’s three tasks (setting the stage, inviting participation, and responding productively) while maintaining awareness of the organization’s current state in the midst of changing circumstances.

Leader Action Steps - Responding Productively

Genuinely express appreciation to team members for participation.

Give constructive feedback, empower others to take action towards company goals, and open dialogue to drive next steps.

Ensure standards are known and team members are held accountable for clear violations. Stay true and consistent with how you “Set the Stage.”

Maintain awareness of what zone your organization is operating out of and strive for excellence found within the “Learning Zone.”

As I reflect back on my dreadful “Maintenance Monday” meetings, I realize that the Army can be an intimidating place to work considering what is at stake to deploy, fight, and win our nation’s wars. Most organizations do not share this same intense mission.

However, I do know that most, if not all, teams have an innate desire to win. And leaders must bring out the very best of their team members in order to achieve victory. While winning could look very different for organizations, fostering an environment of psychological safety helps bring uniquely distinct and valuable souls together towards a common cause. In today’s day and age, this type of leadership is much desired and needed in our modern workplace. As leaders, we have a duty and responsibility to genuinely care for our team members and shepherd them to safety so they can operate at their highest potential to make a difference in this world.

And to me, that sounds a lot like winning.

Life is short - let’s go make it count!

One last thing…If you’re interested in growing in your leadership practice and being inspired to think differently and unlock greater personal potential, we want to give you a gift. Just click the link below and tell us where to send you 12 Ideas That Will Make You A Better Leader In 2022.